di Alessandro Premier

Recenti ricerche stanno dimostrando la validità dei materiali tessili per la realizzazione di manufatti progettati attraverso il design parametrico. In particolare l’abbinamento fra questa modalità di progettazione e l’uso di materiali innovativi sembra essere sempre più frequente.

“La progettazione parametrica (parametric design) è un processo basato sul pensiero algoritmico che consente l’espressione di parametri e regole che, insieme, definiscono, codificano e chiariscono la relazione tra l’intenzione e la risposta progettuale” (W. Jabi, 2013). Si tratta di un modello operativo in cui la relazione tra gli elementi viene utilizzata per manipolare il disegno di geometrie e strutture complesse. Oggi il termine è sostanzialmente riferito ai sistemi di progettazione computazionale (computational design systems), cioè in grado di modellare, simulare o replicare forme/modelli utilizzando un computer. Questo termine è stato utilizzato già negli anni Sessanta del secolo scorso dall’architetto Luigi Moretti (1906-1973) e dal matematico Bruno De Finetti (1906-1985). Tracce di questa modalità progettuale sono contenute nel lavoro del tedesco Frei Otto (1925-2015) e successivamente, in modo più strutturato in Zaha Hadid (1950-2016), Gregg Lynn, ONL e molti altri. In sostanza la tecnologia informatica ha fornito ai progettisti gli strumenti per analizzare e simulare la complessità osservata in natura e applicarla alle forme degli edifici e all’organizzazione urbana.

Fondamentali sono perciò i software a disposizione dei progettisti. Tra i più noti vi sono CATIA (celebre per essere stato utilizzato da Frank Gehry), 3D Studio Max, Maya, Rhinoceros e il suo plug-in Grasshopper 3D. Tutti software molto utilizzati a livello globale tanto che gli studi di architettura più noti (ad es. UNStudio, MVRDV, OMA, SOM) ne richiedono la conoscenza nelle loro offerte di lavoro. La maggior parte di questi software offre un ambiente di modellazione interattivo dove la forma dell’oggetto è ottenuta secondo una logica additiva. Alcuni software offrono delle forme base (ad es. solidi) dalle quali è possibile ricavare oggetti più complessi applicando ad essi delle regole precise (ad es. 3D Studio Max). Altri, dedicati in modo specifico all’edilizia, lavorano con delle librerie di oggetti ai quali sono applicati dati parametrici (ad es. Revit). Il problema principale di questi software è la realizzazione di forme complesse, ad esempio quelle organiche che si ispirano alla natura. Nel software Rhinoceros le entità geometriche (punti, linee, angoli, piani…) sono rappresentate mediante NURBS (acronimo di Non Uniform Rational B-Splines). Le NURBS sono una rappresentazione matematica mediante la quale è possibile definire accuratamente geometrie 2D e 3D quali linee, archi e superfici a forma libera. In sostanza gli oggetti vengono quindi modellati plasmando delle superfici: questo permette di modificare a piacimento qualsiasi forma. In Rhinoceros la progettazione parametrica viene introdotta con il plug-in Grasshopper. Grasshopper consente di configurare e manipolare i legami parametrici che organizzano un modello tridimensionale esclusivamente attraverso un diagramma. In pratica la forma non è più ottenuta secondo una logica additiva o di manipolazione virtuale, ma è generata attraverso una sequenza ordinata di istruzioni: cioè un algoritmo. L’algoritmo è un procedimento che risolve un determinato problema attraverso un numero preciso di istruzioni elementari. In Grasshopper quindi non troviamo più il classico ambiente di modellazione interattivo bensì uno spazio di lavoro dove costruire l’algoritmo in grado di generare la forma dell’oggetto. Il modello diventa quindi dinamico, cioè in grado di essere rielaborato continuamente inserendo o sostituendo le istruzioni un po’ come avviene nel processo progettuale classico, ad esempio attraverso gli schizzi. Per questo motivo si parla proprio di progettazione parametrica e non semplicemente di modellazione. Questo sistema, detto “nodale”, prevede quindi una serie di input e un algoritmo che combina gli imput stessi per ottenere la forma dell’oggetto.

Negli ultimi decenni, la realizzazione di edifici temporanei ha rappresentato probabilmente il principale ambito di sperimentazione teorica e pratica per quanto riguarda l’implementazione della progettazione parametrica. Anche per questo motivo numerose sono le applicazioni di materiali tessili per schermi e rivestimenti fissi. In linea generale, per questo tipo di interventi, possiamo distinguere tre tipologie di rivestimenti e schermi (Cfr. Schock H.J, 2001, p. 30): a) tessuti spalmati; b) tessuti non spalmati; c) film. La progettazione parametrica consente anche di definire i singoli elementi che costituiscono il rivestimento. Questi possono avere un pattern regolare (ad es. tassellatura a poligoni: triangoli, esagoni ecc.), irregolare o misto.

I rivestimenti con tessuti spalmati (impermeabilizzati) sembrano essere i più frequenti. Tra i vari esempi troviamo il celebre Burnham Pavilion progettato da Zaha Hadid. Il padiglione fu collocato nel centro di Chicago allineato secondo la diagonale del piano urbanistico della città redatto da Daniel Burnham nel 1909. Il padiglione fu infatti realizzato per celebrare i 100 anni del piano. La struttura portante era in tubolari di alluminio curvati. Il rivestimento era realizzato con porzioni di tessuto saldate fra loro e tensionate sul telaio per creare la forma curvilinea. La pelle interna invece era utilizzata come schermo per una video installazione di Thomas Gray che esplorava il passato e il futuro di Chicago. Il padiglione fu progettato per essere spostato successivamente nel Millennium Park (sempre a Chicago), con la possibilità comunque di essere smontato e reinstallato in altri siti. Il manufatto aveva un’altezza massima di circa 6 metri. Il telaio era rivestito con due membrane: una esterna e una interna. Il tessuto esterno era in poliestere spalmato in PVC (materiale ampiamente usato per tensostrutture) mentre quello interno, che ospitava proiezioni luminose, era in fibra di poliestere non spalmata. L’ancoraggio del tessuto esterno alla struttura metallica era effettuato mediante fune passante su occhielli. I lucernari invece erano chiusi mediante un film trasparente in vinile.

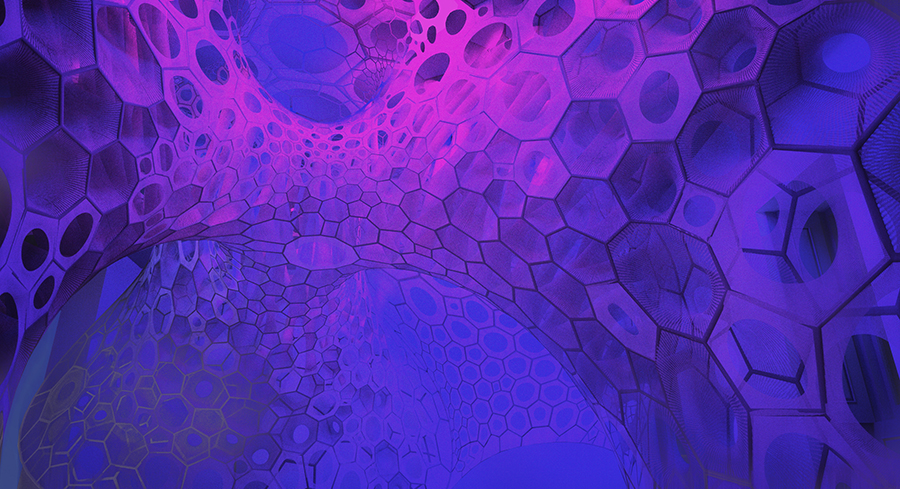

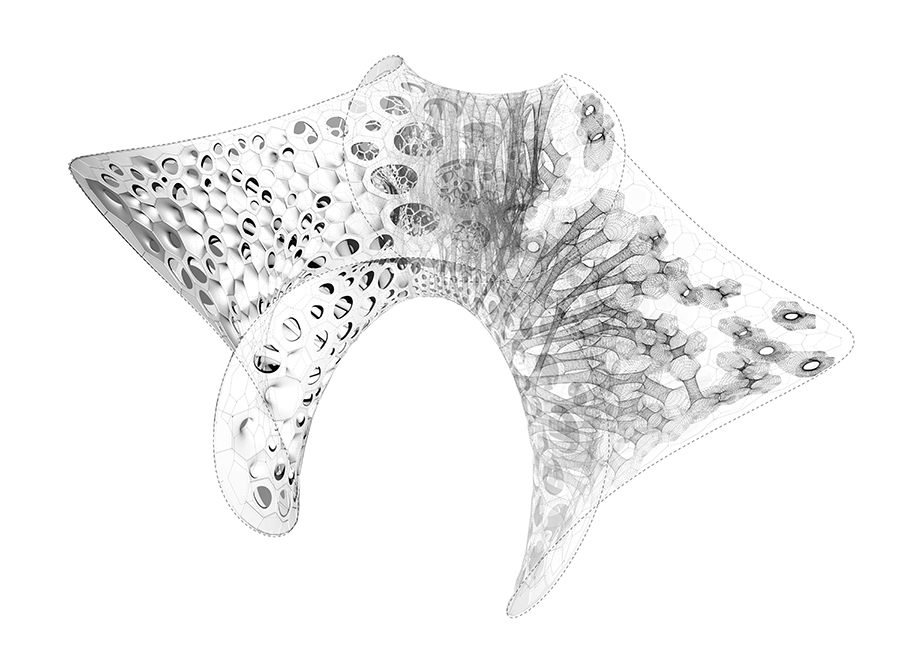

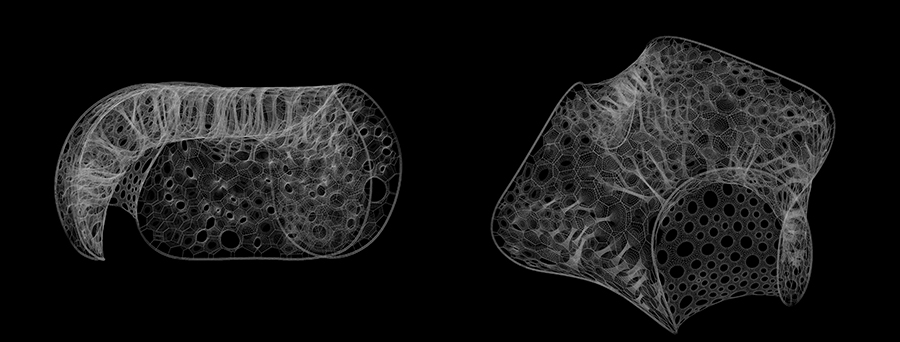

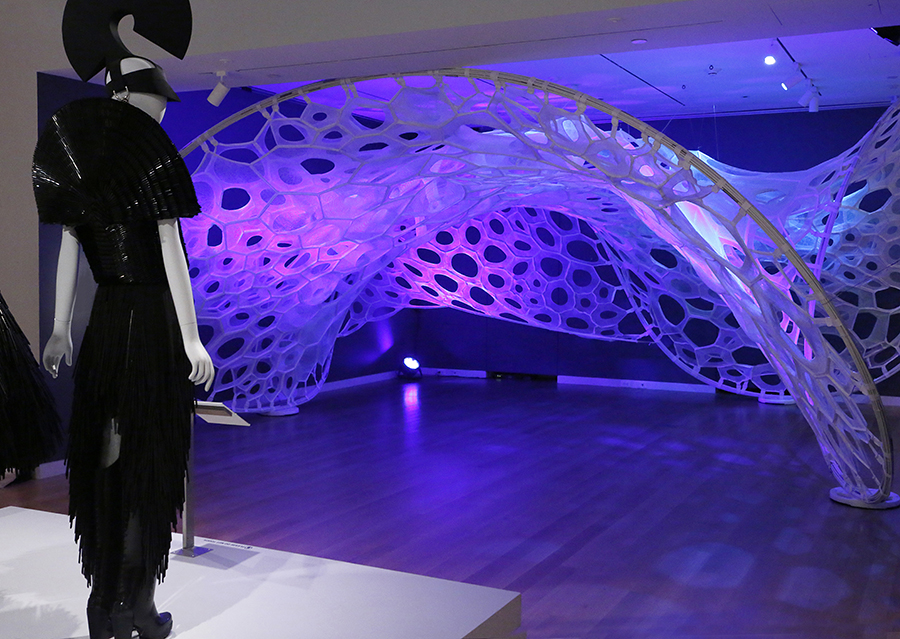

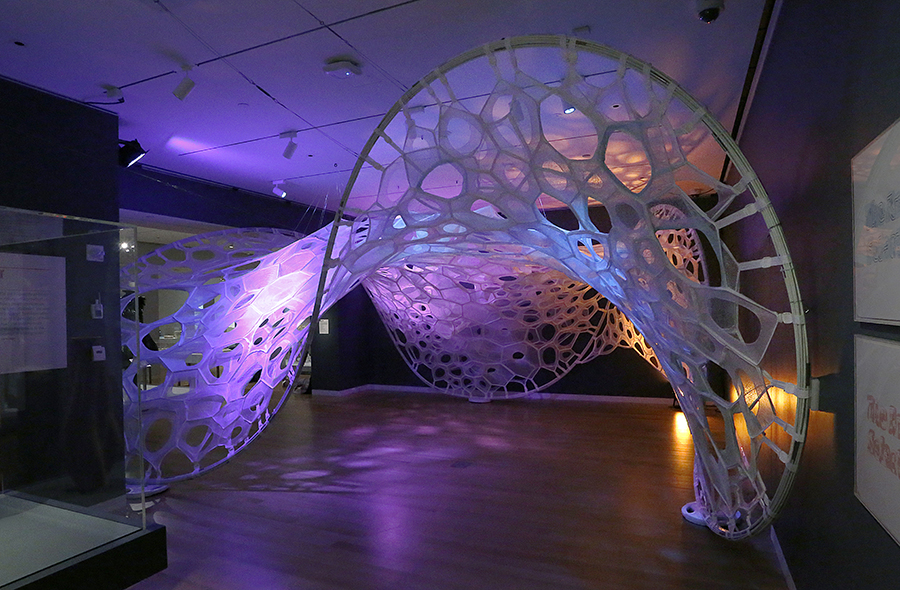

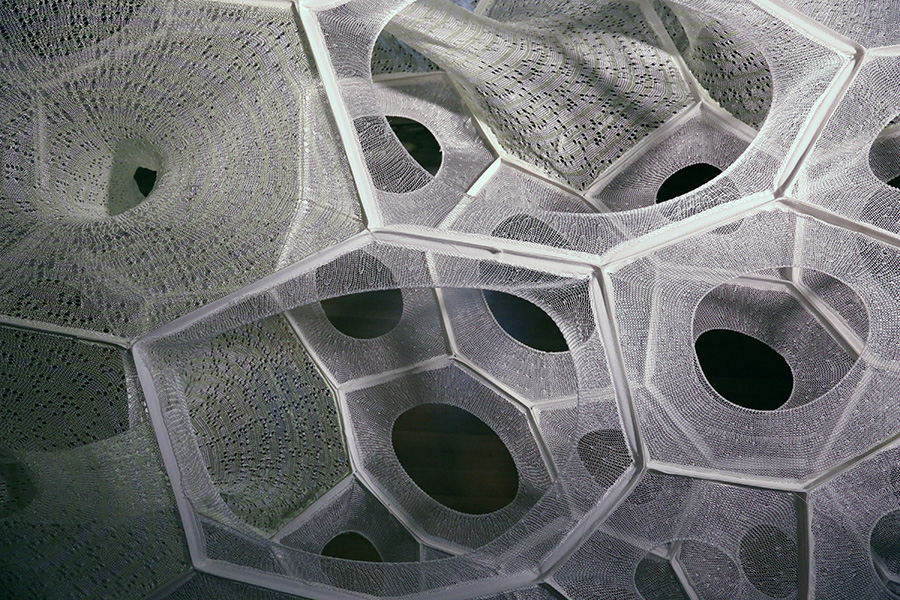

Un’applicazione innovativa di tessuti non spalmati è rappresentata invece dal PolyThread Textile Pavilion. Dal 12 febbraio al 21 agosto 2016 il Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum di New York ha ospitato la quinta edizione della sua triennale dedicata al design (Beauty-Cooper Hewitt Design Triennial 2016). Il tema di fondo dell’esposizione era la “bellezza” con un focus sull’innovazione “estetica”. L’esibizione ospitava più di 250 lavori realizzati da 63 diversi designers e studi internazionali. I progetti esposti erano suddivisi in sette sezioni: stravaganti, intricati, eterei, trasgressivi, emergenti, elementari e trasformativi. Per la sezione “emergenti” – una selezione di progetti che impiegavano sistemi digitali per generare forme inaspettate – lo studio Jenny Sabin ha concepito il Polythread Knitted Textile Pavilion, letteralmente traducibile con padiglione in tessuto lavorato a maglia. La costruzione architettonica del padiglione si ispira sia alla natura (strutture cellulari) che alla matematica ed è realizzata attraverso l’assemblaggio di diversi elementi: parti tridimensionali tessute a maglia digitalmente, filati fosforescenti e in polipropilene, nastro spigato e tubi in fibra di vetro. Il padiglione temporaneo impiega filati con pigmenti fotoluminescenti che si attivano con la luce e sono in grado di assorbire, conservare e trasmettere luce. Dal punto di vista pratico il padiglione è super-leggero e trasportabile e può essere utilizzato all’aperto per assorbire la luce del sole di giorno e rilasciarla di notte.

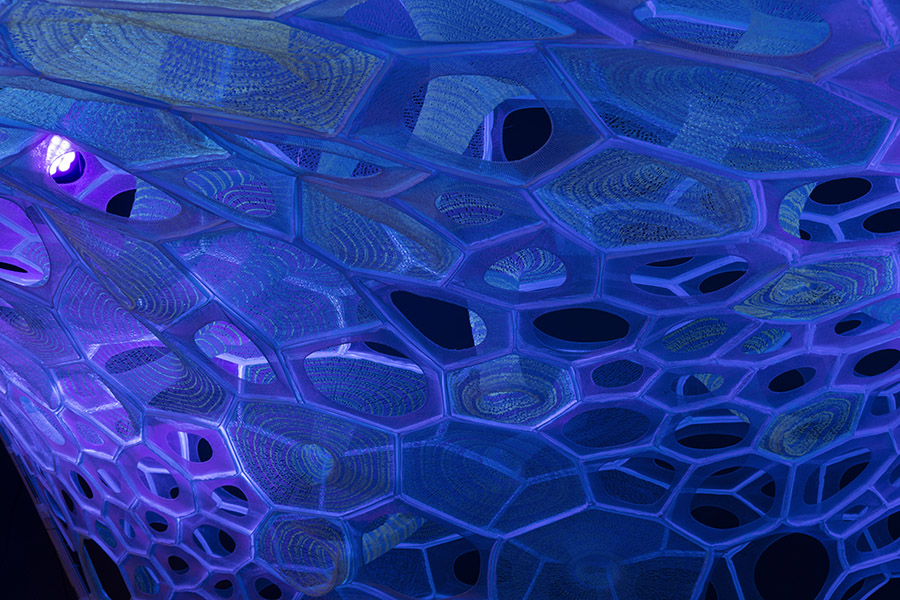

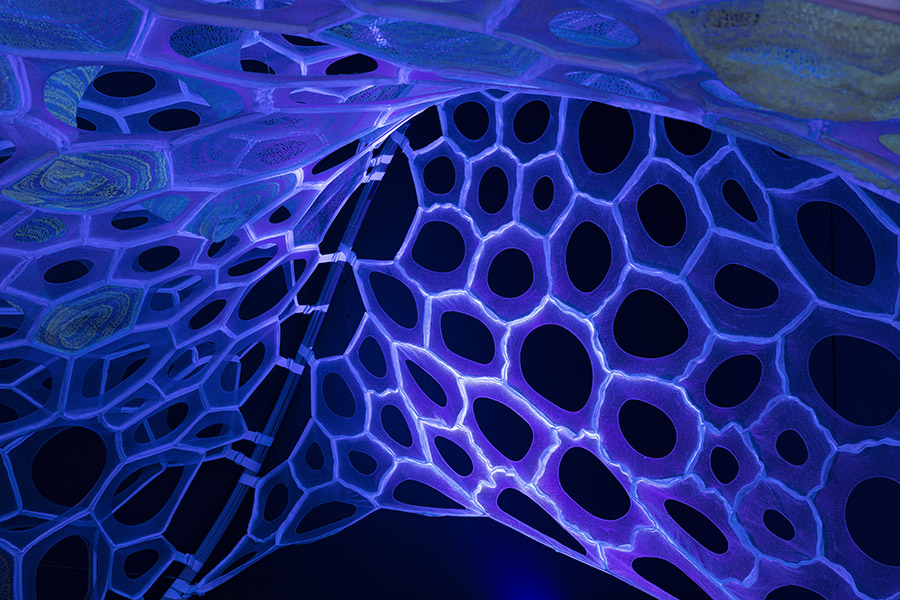

L’installazione, commissionata direttamente dal Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum, esplora le connessioni fra architettura, matematica e materiali leggeri. La struttura in fasci di tubi in fibra di vetro costituisce la forma base che permette al padiglione di reggere se stesso e il tessuto. La forma complessiva del padiglione è quella di una cupola increspata. La struttura è alta circa due metri nel punto più basso e tre metri in quello più alto. Come già evidenziato, le forme e le geometrie si ispirano alla natura: in particolare il tessuto è costituito da una struttura esagonale a nido d’ape. I filati fotoluminescenti corrono lungo la trama a nido d’ape evidenziandone il pattern. Ogni esagono è costituito da una maglia forata.

La copertura è costituta da due membrane sovrapposte collegate alla struttura portante mediante cinghie regolabili. Elementi “a collo” collegano le due membrane. Per la mostra, il passaggio dal giorno alla notte era simulato con l’ausilio di tre proiettori Elation SIXPAR 200IP con 12 LED da 12W 6-in-1. Gli apparecchi collegati in serie erano controllati da un ETC Express Lighting Playback Controller (LPC), un regolatore di riproduzione luminosa che gestiva la sequenza di accensione giorno-notte. Una variazione cromatica della luce dal blu al rosa pallido sottolineava questo passaggio. Il padiglione è stato concepito come una potenziale soluzione per portare l’illuminazione artificiale in alcune parti del mondo dove la fornitura di energia elettrica è scarsa o nulla. Il progetto architettonico è di Jenny E. Sabin di Jenny Sabin Studio con Martin Miller e Charles Cupples ed è il frutto di una ricerca scientifica condotta presso il Sabin Design Lab della Cornell University, College of Architecture, Art, and Planning, dove Jenny Sabin è ricercatrice universitaria. I tessuti sono del tipo WholeGarment, prodotti da Shima Seiki. L’ingegnerizzazione è di Arup. Il finissaggio dei tessuti è di Andrew Dahlgren. Cucitura e assemblaggio sono di All Sewn Together LLC. In particolare, “la maglieria WholeGarment è realizzata già completa in un solo pezzo, tridimensionale, direttamente sulla macchina rettilinea. Di conseguenza, non occorre tutto il lavoro di confezione in post-produzione” (Cfr. www.shimaseiki.eu).

Questo tipo di tessuti senza cuciture consente di avere un pattern privo di interruzioni lungo tutto il capo riproducendo esattamente il disegno previsto dal progettista. L’assenza di cuciture consente maggiore elasticità e mobilità della maglia. La conformazione in un pezzo unico senza cuciture permette inoltre allo sforzo eventuale di distribuirsi in modo uniforme, prevenendo pressioni localizzate in punti specifici. Nella catena di produzione viene eliminata la parte di taglio e cucito, eliminando anche gli scarti e ottimizzando l’uso della risorsa primaria. Questo metodo di fabbricazione consente di calcolare al meglio i tempi, perfezionando la produzione a richiesta, anche perché i pezzi sono realizzati basandosi su dati elettronicamente programmati e memorizzati mantenendo una qualità costante anche su lotti diversi. Il progetto rappresenta un approccio sperimentale nell’ambito della fabbricazione digitale dell’architettura, con l’elaborazione di modelli e prototipi mediante software parametrici e associativi e l’interfaccia con tecnologie costruttive innovative e discipline correlate ma alternative.

In conclusione possiamo affermare che il design parametrico, realtà sempre più diffusa negli studi di architettura internazionali, rappresenta, assieme al BIM e ad altre tecnologie odierne, non solo una modalità di controllo del progetto ma anche un sistema di rielaborazione costante dello stesso per giungere ad un risultato finale che consenta anche una gestione ottimale delle componenti costruttive. In questa logica i materiali tessili rappresentano una soluzione ottimale per la materializzazione degli involucri complessi progettati secondo questo approccio procedurale. Nei progetti citati abbiamo visto che la destinazione d’uso e il livello di sperimentazione del manufatto consentono l’impiego di materiali diversi. Quando si ha a che fare con un manufatto di pubblico utilizzo con dei requisiti ben definiti di durabilità, resistenza ecc. (ad es. Burnham Pavilion) si predilige l’utilizzo di materiali con prestazioni controllate (tessuti spalmati ecc.). Quando si può sperimentare e fare ricerca (PolyThread Pavilion), soprattutto nell’ambito delle installazioni artistiche ma anche dei manufatti per l’interior design, è possibile impiegare combinazioni di tessuti diverse e sperimentare il trasferimento tecnologico di materiali provenienti da altri settori (tessuti con fibre miste ecc.). La sperimentazione, che oggi avviene perlopiù nei centri di ricerca e universitari dotati di idonee strutture, consente inoltre di individuare soluzioni innovative che in un futuro assolutamente prossimo si possono trasformare in interessanti occasioni applicative e di potenziale business.

Riferimenti bibliografici

Jabi W., Parametric Design for Architecture, Laurence King, London, 2013.

Schock H.J., Atlante delle tensostrutture, UTET Scienze Tecniche, Torino, 2001.

Pocewicz A., “The Burnham Pavilion in Chicago Redefines Fabric Architecture” in blendconcepts.com

Alessandro Premier, architetto, dottore di ricerca in Tecnologia dell’Architettura, consegue il PhD con la ricerca “Zona mobile. Tecnologie per l’integrazione architettonica di elementi schermanti mobili”. Docente a contratto di Tecnologia dell’Architettura presso l’Università di Udine, Dipartimento Politecnico di Ingegneria e Architettura, Corso di Laurea in Scienze dell’Architettura, ha insegnato presso l’Università Iuav di Venezia e tenuto seminari presso il Politecnico di Milano. Socio fondatore del Centro Ricerche “Eterotopie. Colore, luce e comunicazione in architettura” ha all’attivo oltre 100 pubblicazioni sui temi di ricerca, tra le quali si segnala il libro Superfici Dinamiche. Le schermature mobili nel progetto di architettura, Franco Angeli, Milano, 2012.

Attualmente è docente presso l’Università di Auckland.

Parametric design in the creation of screening fabrics

Recent studies are showing the value of textile materials used in the production of parametrically designed artifacts. Indeed, it seems that using the parametric design technique in combination with innovative materials is becoming an increasingly frequent practice.

“Parametric design is a process based on algorithmic thinking that enables the expression of parameters and rules that, together, define, encode and clarify the relationship between design intent and design response” (W. Jabi, 2013). It is an operational model in which the relationship between the elements is used to manipulate the design of complex geometries and structures. Nowadays the term mainly refers to computational design systems, in other words systems capable of modelling, simulating or replicating shapes and patterns using a computer. The term was actually used early as the 1960s by architect Luigi Moretti (1906-1973) and mathematician Bruno De Finetti (1906-1985). Traces of this design method can be found in the work of German Frei Otto (1925-2015) and later, in a more structured manner, in Zaha Hadid (1950-2016), Gregg Lynn, ONL, and many others. Basically, information technology has given designers the instruments to analyse and simulate the complexity of nature, and apply it in the shaping of buildings and in urban organisation.

A crucial role is therefore played by the software available to designers. The best known packages include CATIA (famous for having been used by Frank Gehry), 3D Studio Max, Maya, and Rhinoceros, with its plug-in Grasshopper 3D. All these are widely used globally, so much so that the leading architectural firms (e.g. UNStudio, MVRDV, OMA, SOM), when advertising vacancies, specify that applicants must be familiar with them. Most of them provide an interactive modelling environment in which the shape of the object being designed is obtained as the result of additive logic. Some packages (such as 3D Studio Max) offer basic shapes (e.g. solids) from which, by applying precise rules, more complex objects can be derived. Others, specifically devoted to building (e.g. Revit), work with object libraries to which parametric data are applied. The main difficulty encountered when using this kind of software concerns the realisation of complex shapes, such as organic ones inspired by nature. In Rhinoceros, the geometric elements (points, lines, angles, planes and so on) are represented through NURBS (an acronym standing for non-uniform rational B-splines). NURBS are mathematical representations that can be used to accurately define 2D and 3D geometries, such as lines, arcs and free-form surfaces. Basically, the objects are then formed by modelling surfaces: in this way, any shape can be modified as desired. In Rhinoceros, parametric design is made available through Grasshopper. This plug-in allows you, through a simple diagram, to configure and manipulate the parametric constraints that represent the organisational basis of a three-dimensional model. In practice, the shape is no longer obtained according to additive or virtual manipulation logic, but rather generated through an ordered sequence of instructions, i.e., an algorithm. An algorithm is a procedure that solves a given problem through a precise number of elementary instructions. In Grasshopper, therefore, we no longer find the traditional interactive modelling environment, but instead a workspace in which to build an algorithm capable of generating the shape of the object. The model thus becomes dynamic, in the sense that it can be re-elaborated continuously by inserting or replacing instructions, in a manner akin to what is seen classic design process, with sketches for example. This is why we talk of parametric design rather than simply modelling. This system, defined “nodal”, thus involves a series of inputs and an algorithm that combines the inputs themselves to obtain the shape of the object.

The construction of temporary buildings has, in recent decades, probably been the main area of theoretical and practical experimentation in parametric design. This is one of the reasons why there exist numerous applications of textile materials for fixed screens and coverings. The materials used in these applications can basically be divided into three types (Cf. Schock H.J, 2001, p. 30): a) coated fabric; b) non-coated fabric; c) film. Through parametric design it is also possible to define the single elements making up the covering, whose pattern may be regular (e.g. a tessellation of regular polygons: triangles, hexagons, etc.), irregular or mixed.

Coverings made from coated fabrics (waterproof) seem to be the most common. Among various examples we find the famous Burnham Pavilion designed by Zaha Hadid. This installation was erected in downtown Chicago, aligned with a diagonal in the plan of the city drawn by Daniel Burnham in 1909. In fact the pavilion was built to mark the 100th anniversary of this plan. Its supporting structure consisted of curved aluminium tubes, while the covering was formed by pieces of fabric welded together and stretched over the frame to give the pavilion its curvilinear shape. The interior skin was used as a screen for a video installation by Thomas Gray that explored the past and future of Chicago. The pavilion was specifically designed in such a way that it could be moved, subsequently, to Millennium Park (also in Chicago), and in any case dismantled and reassembled at other sites. The artifact stood six metres tall at its highest point. Its frame was covered with two membranes: one external and one internal. The external fabric was PVC-coated polyester (extensively used for tensile structures) while the internal one, on which the images were projected, was made from uncoated polyester fibres. The external fabric was anchored to the metallic structure by means of ropes threaded through eyelets, while the skylights are made of transparent vinyl film.

The PolyThread Textile Pavilion, on the other hand, provides an innovative example of the use of non-coated fabrics. From February 12 to August 21, 2016, the Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum in New York hosted its fifth design triennial (the Beauty-Cooper Hewitt Design Triennial 2016). The underlying theme of the event was “beauty” and it focused in particular on “aesthetic” innovation. It hosted more than 250 works by 63 different designers and international firms. The exhibits were divided into seven themes (extravagant, intricate, ethereal, transgressive, emergent, elemental and transformative). For the “emergent” section – a selection of projects in which digital systems were used to generate unexpected shapes –, the Jenny Sabin Studio produced the PolyThread Knitted Textile Pavilion, which, as its name indicates, was a knitted fabric installation. Inspired by nature (cellular structures) and mathematics, this architectural construction was obtained by assembling different elements: digitally woven 3D parts, phosphorescent, polypropylene yarns, herringbone tape and glass fibre tubes. The photo-luminescent, solar-active yarns used were able to capture, store and deliver light. From a practical perspective, this temporary installation was super-light and transportable and suitable for use outdoors, being able to absorb the sunlight during the day and then release it at night.

The installation, commissioned directly by the Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum, was an exploration of the links between architecture, mathematics and lightweight materials. The structure was made from bundles of glass fibre tubes and assumed the basic shape that defined the pavilion and allowed it to support itself and the fabric. Basically, it had the shape of a rippled dome. The structure was around two metres high at its lowest point and stood three metres tall at its highest. Its shapes and geometries were inspired by nature: in particular, the fabric featured a hexagonal honeycomb structure. Photo-luminescent yarns followed the honeycomb weave, picking out its pattern. Each hexagon consisted of a perforated mesh. The covering consisted of two overlapping membranes connected to the supporting structure by adjustable straps. “Flanged” elements were used to connect the two membranes.

During the exhibition, the transition from day to night was simulated with the help of three Elation SIXPAR 200IP floodlights with twelve 12W 6-in-1 LEDs. These fixtures, connected in series, were controlled by an ETC Express Lighting Playback Controller (LPC), or light reproduction controller, that managed the sequence of day-night transitions. Each transition was signalled by a change in the colour of the light from blue to pale pink. The pavilion was designed as a potential artificial lighting solution for use in parts of the world that have very little or no access to an electricity supply. The installation was designed by Jenny E. Sabin, of the Jenny Sabin Studio, together with Martin Miller and Charles Cupples, and it is the result of scientific research conducted at the Sabin Design Lab at Cornell University, College of Architecture, Art, and Planning, where Jenny Sabin is a university researcher. It was produced using Shima Seiki WholeGarment® fabric, finished by Andrew Dahlgren, and the engineering design was by Arup. The sewing and assembly were done by All Sewn Together LLC. In particular, “A WholeGarment knit fabric is manufactured in one single piece, three-dimensionally, directly on the knitting machine. Consequently it requires no expensive, time-consuming post-production labour” (see http://www.shimaseiki.com/wholegarment). With seamless fabrics of this kind it is possible to obtain a fabric where there are no interruptions in the pattern at all, with the result that the design envisaged by the designer is reproduced exactly. The lack of seams also makes for a more flexible and elastic weave. A further advantage of the one-piece seamless construction is that any stress to which the fabric is subjected is distributed evenly, avoiding straining of specific areas. Furthermore, without the cutting and sewing stages, the production process is simplified and there is no fabric waste, which means optimal use of the primary resource. This manufacturing method allows more efficient calculation of times and greater accuracy of the production process, given that the pieces are produced on the basis of electronically programmed and stored data, ensuring constant quality even across different batches. This project may be seen as an experimental approach within the field of digital architectural production, involving the development of models and prototypes, using parametric and associative software and interfacing with innovative construction technologies and related but alternative disciplines.

In conclusion we can say that parametric design, an increasingly popular approach in international architectural firms, alongside BIM and other modern technologies, is not just a means of controlling a project, but also a system that allows its constant re-elaboration, so as to arrive at a final result that also ensures optimal management of the construction elements. From this perspective, textile materials represent the ideal solution for realising complex envelopes designed using this procedural approach. In the projects mentioned here, we have seen that different types of material can be used, depending on the intended use and the level of testing of the installation. In the case of an installation for public use, with very specific requirements in terms of durability, strength etc. (e.g. Burnham Pavilion), materials with controlled performance levels (coated fabrics etc.) are preferred. Instead, when the aim is to experiment and carry out research (PolyThread Pavilion), especially in the area of artistic installations but also of interior design artifacts, it is possible to use combinations of different fabrics and experiment with the technological transfer of materials from other fields (mixed fibre fabrics and so on.). Through experimentation, currently largely conducted in research centres and universities equipped with suitable facilities, it is also possible to identify innovative solutions that may, in the very near future, be transformed into interesting applications and potential business opportunities.

Bibliography

Jabi W., Parametric Design for Architecture, Laurence King, London, 2013.

Schock H.J., Atlante delle tensostrutture, UTET Scienze Tecniche, Torino, 2001.

Pocewicz A., “The Burnham Pavilion in Chicago Redefines Fabric Architecture” in blendconcepts.com

Alessandro Premier is an architect and PhD holder in architectural technology. His PhD was awarded for research into “The mobile zone. Technologies for the architectural integration of mobile screening elements”. He is adjunct professor on the Master’s degree course in Architecture at Udine University, Department of Civil Engineering and Architecture. He has taught at the Iuav University of Venice and held seminars at the Politecnico di Milano. He is a founding member of the “Eterotopie – Colour, Light and Communication in Architecture” Research Centre and has authored more than 100 publications on research topics, including a book entitled Superfici Dinamiche. Le schermature mobili nel progetto di architettura (Dynamic Surfaces. Mobile Screens in Architectural Projects), Franco Angeli, Milano, 2012. He is currently a lecturer at the University of Auckland.