Di Katia Gasparini

Gli schermi, i ripari dalle intemperie e dal sole sono parte imprescindibile della storia umana fin dall’antichità: dai primitivi ripari realizzati con materiali naturali, foglie e sterpaglie, ai primi tessuti grezzi delle epoche ante era volgare. In effetti i primi tessuti sembra risalgano al Neolitico. Le prime fibre utilizzate per i tessuti della preistoria erano di tipo vegetale, venivano ricavate dal libro di alcuni alberi, ossia quel tessuto che trasporta la linfa dalle radici alla foglia e i frutti. Gli alberi che fornivano quelle migliori erano olmo, salice, quercia e tiglio, ma anche l’ortica e il lino. Originariamente si trattava di tessuti per abbigliamento.

L’uso del tessuto come riparo dall’irraggiamento o anche solo di decoro risale a epoche più recenti, rispetto la storia dell’uomo. Le testimonianze pittoriche e iconografiche sui velarium ci rimandano ai mosaici bizantini, come il Mosaico Praeneste dell’80 a.E.V. che rappresenta un grande velo che scende dal frontone di un tempio e forma una sorta di baldacchino, sostenuto da pali in legno, a riparo dell’area antistante. Successive rappresentazioni si sono scoperte a Pompei e sono proseguite anche nei velarium utilizzati nelle arene per schermare dal sole, rappresentati anche nella colonna Traiana.

In epoca contemporanea gli esempi più popolari sono quelli dei mercatini rionali che da tempi immemorabili si svolgono nelle piazze dei mercati e lungo le strade dei paesi, che appartengono un po’ a tutte le culture.

In effetti, in epoca contemporanea questa esigenza di schermare le attività espositive e commerciali si è trasferita e trasformata in ambito urbano in maniera più estesa e colorata. Sono cambiate le abitudini dell’uomo, le facciate degli edifici con le loro attività commerciali sembra abbiano sostituito i più artigianali mercatini e le tende diventano un intervento di arredo urbano, spesso delle installazioni artistiche. Quello che oggi rientra nell’ambito dell’urban design, spesso pensato come installazione artistica site specific, in realtà ha origini lontane nella storia, in cui assolveva a funzioni ben precise.

I tessuti tecnici sono così utilizzati per installazioni artistiche colorate presenti nelle maggiori città europee. Contemporaneamente schermano e rendono piacevole la passeggiata turistica nelle vie principali. Si tratta per lo più di tende a vela disposte lungo le direttrici turistiche cittadine, soprattutto nelle città più calde, come per esempio a Madrid.

Nel centro storico della città è possibile vedere un’installazione realizzata con tessuto filtrante nei toni dei verdi e dei blu, colori freddi che schermano e assorbono parte della radiazione luminosa (fig.1).

Infatti non sono nuove le installazioni con ombrelli colorati lungo le vie, iniziate ad Águeda in Portogallo nel 2012, ma realizzate anche in alcune cittadine italiane come Pietrasanta, Zagarolo, Arona e così via.

Oggi quindi, tessuti e teli prendono forma per diventare rivestimenti leggeri di facciata, sistemi mobili di ombreggiamento, installazioni effimere, strutture temporanee, sinuose architetture di interni o grandi coperture traslucenti.

Il tema dell’integrazione dei sistemi ombreggianti in ambito urbano e quelli schermanti negli edifici è assolutamente attuale perché definisce la qualità ambientale dello spazio urbano e, perché no, anche l’orientamento degli utenti attraverso forme e colori (way-finding). In effetti, come sostiene Premier, “ciò che determina a livello percettivo la qualità di questi spazi sembra essere in prevalenza ciò che riusciamo a cogliere visivamente. E ciò che riusciamo a cogliere degli spazi attraverso la vista è in genere la qualità superficiale delle cose” (Premier A., 2012). Ecco quindi perché le superfici schermate o le schermature orizzontali, come quelle anzi menzionate, rivestono una tale importanza nella configurazione e qualificazione degli spazi urbani.

Le vele colorate sono l’elemento chiave del progetti di riqualificazione di Piazza Faber a Tempio Pausania, nel 2016. Il progetto, a cura di Alvisi Kirimoto + Partners e Renzo Piano, consta di una varietà di vele di tela colorate che fluttua nel cielo del centro del paese a realizzare una installazione leggera e mutevole. Il progetto celebra la luce e il colore del paesaggio della Gallura con un intervento di valorizzazione della piazza del mercato. L’intervento è dedicato al cantante Fabrizio De André che aveva scelto la Gallura come suo ritiro. L’installazione è composta di una serie di 12 elementi sospesi, che sullo sfondo hanno la cortina di edifici storici, fra cui emergono le arcate del vecchio mercato, quasi a tornare all’antico legame fra i mercati e le schermature di cui si accennava. Le vele sono realizzate in tessuto Soltis di Serge Ferrari®.

Sull’onda di queste iniziative e sviluppi creativi, il Subrella® Contest del 2016 “ Future of Shade”, in collaborazione con Architizer , ha invitato i designer e gli architetti a creare nuove visioni concettuali nel design delle schermature utilizzando il tessuto Sunbrella per tre categorie: brise soleil, benessere egli spazi aperti e ambito umanitario.

I molti progetti presentati hanno utilizzato il colore e la luce naturale come strumenti di progetto, giocando sulla traslucenza e semitrasparenza dei tessuti o, al contrario, sui contrasti cromatici per valorizzare i percorsi.

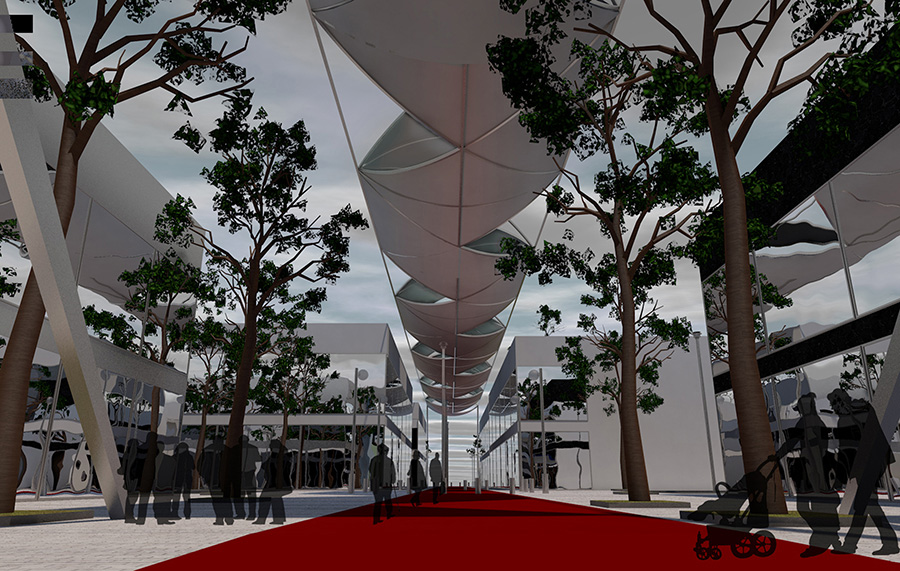

Fra questi, il progetto I-Shade presentato dal gruppo Eterotopie (P.Zennaro, K.Gasparini, A.Premier). Il sistema schermante concepito mirava a completare il design del Miami Design District con un sistema di copertura schermante modulare e ripetibile, dalla configurazione di superficie variabile, secondo i tessuti e la luminosità. Il sistema è stato proposto in due varianti, su due fronti diversi: Paradise Plaza e Paseo Ponti.

Il sistema strutturale si basava su un modulo quadrato 30×30 piedi, modulare e ripetibile, la cui sezione in elevazione è generata dalla intersezione di due circonferenze uguali. Si configura in questo modo una struttura reticolare tubolare realizzata in profili di acciaio alla quale possono essere ancorati dei tessuti tesi per generare una schermatura solare. L’intera struttura è sospesa tramite puntelli in acciaio alle due estremità, in modo da non interferire con la visione delle vetrine dei negozi.

Il design si basa sul concetto di Hyper-Architettura dove fluidità e dinamismo sono le parole chiave: una ragnatela modificabile che fa da base allo sviluppo dell’architettura.

Il rivestimento tessile è l’elemento che caratterizza una delle due coperture di Paradise Plaza rispetto quella del Paseo Ponti. In Paradise Plaza l’involucro tessile avvolge completamente lo scheletro strutturale posto lungo l’asse est-ovest. Il modulo tessile di colore bianco è caratterizzato da pieni e vuoti in modo lasciare filtrare la luce, l’aria ed eventualmente anche i rami degli alberi previsti nella piazza. I fori dalle geometrie fluide, oltre a creare un design distintivo per la copertura, creano un gioco di luci ed ombre sulla superficie della piazza.

Su Paseo Ponti, lungo l’asse nord-sud, la copertura tessile realizzata con figure triangolari ancorate alla struttura metallica, si sviluppa come un grande nastro continuo che avvolge tutta la struttura sospesa, lasciando degli spazi vuoti dove può passare la luce. Di notte il tessuto crea un particolare gioco di riflessi con le luci previste lungo il viale (fig. 2-3).

Sperimentazioni più recenti vedono l’installazione di schermature solari fisse in spazi contemporanei, di nuova realizzazione, laddove la schermatura entra nel processo di progettazione dello spazio urbano o, come nel caso dell’attuale Biennale di Architettura di Venezia, diventano installazione artistica.

Nel primo caso rientrano i sistemi ombreggianti installati anche con la funzione di arredo urbano a Lisbona nel relativamente recente Parco delle Nazioni, nello spazio prospicente l’Oceanario (fig. 4).

Qui, una serie di “alberi tessili” che si aprono verso l’alto come ombrelli rovesci di colore giallo/arancione, a base quadrata, poggiano su pilasti bianchi e offrono agli avventori e turisti riparo dal sole cocente della grande piazza. L’intradosso degli “alberi tessili” è illuminato da fari posizionati alla sommità del fusto, rivolti verso l’alto . Il percorso segnato dagli alberi è intervallato da aree di sosta arredate con sedute colorate in cemento a righe nei colori del giallo/blu e del bianco/blu, disposti l’una fronte all’altra come in un ideale salotto urbano.

Il padiglione Danese all’attuale Biennale di Architettura di Venezia, celebra la collaborazione fra gli studi internazionali di BIG, Praksis Arckitecter, CITA e Vandkunsten, dei quali sono stati selezionati i quattro progetti installati all’interno ed esterno del padiglione. Ogni progetto risponde a un argomento specifico che si snoda attorno ai temi dello sviluppo e dell’innovazione futuri, tra cui costruzione, identità, mobilità e nuovi strumenti. L’imponente installazione di CITA (Center for Information Technology and Architecture, centro di ricerca della Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts in Copenhagen) all’ingresso del padiglione dimostra le potenzialità dello sviluppo di nuovi metodi di progettazione e costruzione interdisciplinari digitali.

La forma organica dell’installazione avvolge parte del neoclassico padiglione danese nei Giardini, costituito da tessuti realizzati su misura rinforzati da barre in fibra di vetro. Il sistema ricorda un’elaborata struttura di tenda, il tessuto traslucido e le aste in fibra di vetro si piegano in tensione e compressione per abbracciare il passaggio centrale del padiglione e le parti del suo portico. L’installazione parassita è dipendente dal padiglione, ma è possibile immaginare applicazioni alternative con fondazioni permanenti o come parte di un sistema di facciata integrato. Ogni pannello tessile che costituisce la forma organica è unico, suggerendo la libertà che la modellazione computazionale offre – le variabili di input possono essere spostate a seconda del contesto dato, consentendo di generare infinite iterazioni.

Il nome del progetto, Isotropia, allude all’equilibrio tra struttura, materiale e condizioni del sito. Isoropia utilizza un nuovo strumento software, K2 engineering, per progettare, prevedere, analizzare e perfezionare le prestazioni dei materiali, attenuando le inefficienze riscontrate negli usuali metodi di costruzione. Gli strumenti tradizionali richiedono la prototipazione manuale ad alta intensità di manodopera e il calcolo strutturale iterativo, assegnando l’analisi alle fasi finali. I sistemi di modellazione in fase iniziale consentono di integrare le indagini strutturali e materiali nel processo di progettazione iniziale, rendendo possibile un’architettura in cui i comportamenti materiali siano compresi e applicati attivamente (B.Wells, Arcspace, 2018).

Le tecnologie digitali hanno trasformato rapidamente e radicalmente la nostra capacità di concettualizzare, progettare e fabbricare materiali e forme. Ciò pone molte possibilità per l’innovazione materiale e architettonica, ma richiede anche una fluidità che difficilmente collima con le rigide strutture del settore e la sua tendenza ad assegnare nuovi strumenti a specifici attori e fasi di lavoro limitate.

Cosa succede quando i nuovi strumenti digitali sfidano i tradizionali territori degli attori del settore edilizio e le varie fasi della progettazione e della costruzione iniziano a fondersi e a confondersi? Quando il pensiero architettonico diventa simbiotico con la modellazione computazionale e la fabbricazione materiale, quali possibilità di innovazione si palesano?

URBAN SHADING

Lightness and innovation in urban shading systems

Sun screens, like forms of shelter from inclement weather, have been a constant part of the history of mankind from ancient times: from the first primitive shelters made using natural materials, leaves and brushwood, to the first rough and rudimentary fabrics of the period before the Common Era (BCE). In fact, the earliest fabrics seem to date back to the Neolithic period. In prehistorical times, the first fibres used to make fabrics were vegetable ones, obtained from the phloem of certain trees, that is to say, from the tissue that carries the sap from the roots to the leaves and fruit. The tree species providing the best fibres are the elm, willow, oak and lime, but nettles and flax are also good natural sources. The earliest fabrics were used for clothing. The use of fabric for providing protection against the sun’s rays or even just for decorative purposes dates back to more recent periods in human history. Pictorial and iconographic evidence found on velaria refers us back to mosaics, such as the Praeneste Mosaic dated 80 BCE, which shows a large drape descending from the pediment of a temple and forming a sort of canopy, supported by wooden poles, to shelter the area in front of the building. Subsequent images were discovered in Pompeii. Velaria were also used in later times in arenas to screen the sun’s light as depicted on Trajan’s Column.

The most popular examples from contemporary times are provided by local markets of the kind that have been held in market places and along village streets since time immemorial, and can be found in pretty much all cultures.

In the contemporary era this need to protect display and commercial activities has moved into urban areas, where it has evolved to become a more extensive and colourful phenomenon. People’s habits have changed and building façades, characterised by shops, now seem to have taken over from traditional craft markets. In this context, sun awnings have become design features and often art installations. All elements that today comes under the umbrella of urban design, often conceived as site-specific art installations, actually have roots that go way back in history, to times when they served very specific purposes.

Accordingly, technical textiles now feature prominently in colourful art installations in all Europe’s major cities, where they provide shade but at the same time make walking along the main streets a more pleasant experience for tourists. As a rule, especially in the hottest cities, such as Madrid, they consist of awnings arranged along the city’s main tourist streets.

In the historic centre of Madrid, there is an installation made of filtering fabric in various shades of green and blue, cold colours that provide shade and absorb part of the sun’s radiation (fig.1).

Installations consisting of numerous umbrellas suspended along streets are actually not a novelty, having originated in Águeda, Portugal, in 2012. They can now be seen in several Italian towns, too, such as Pietrasanta, Zagarolo and Arona. In short, it has now become customary for fabrics and drapes to be transformed into lightweight skins for building façades, mobile shading systems, ephemeral installations, temporary structures, sinuous interior design solutions, or large translucent marquees.

The concept of combining urban shading solutions with buildings’ shading systems is a highly topical one, since these are the elements that define the quality of urban spaces, and that, through the careful use of shapes and colours, can even help users to find their way around. Indeed, as remarked by Premier, “on a perceptual level, the quality of these spaces seems to be determined on the whole by what we are able to capture visually. And the main aspect of spaces that we capture through sight is usually the surface quality of the things we see” (Premier A., 2012). This explains why shaded surfaces or horizontal shading systems like the ones we have just mentioned are so important in the configuration and qualification of urban spaces. The redevelopment of Piazza Faber in Tempio Pausania, in 2016, revolved around the use of coloured drapes. Designed by Alvisi Kirimoto + Partners and Renzo Piano, the project is based on various coloured canvas awnings suspended in the sky over the town centre, creating a light and constantly changing installation. Celebrating the light and colour of the Gallura landscape, it is a work designed to enhance the market place, and it is dedicated to the singer Fabrizio De André, who chose Gallura as his personal retreat. The installation is made up of a series of 12 suspended elements set against a backdrop consisting of historical buildings and the archways of the old market, almost as though to underline the ancient link between markets and shading systems mentioned earlier. The awnings are made from Soltis fabric from Serge Ferrari®.

As part of this wave of creative initiatives and developments came the 2016 competition “Future of Shade”, sponsored by Sunbrella® in collaboration with Architizer, which saw designers and architects invited to come up with imaginative new ideas in shading design based on the use of Sunbrella fabric. The competition was split into three categories: building shade, wellness gardens and humanitarian.

The numerous projects submitted used colour and natural light as design tools, playing with the translucency and semi-transparency of the fabrics or, instead, their contrasting colours, in order to enhance particular routes.

They included a project called I-Shade presented by the Eterotopie group (P. Zennaro, K. Gasparini, A. Premier). The aim of the shading system devised by these authors was to complete the design of the Miami Design District environment with a modular and repeatable shading system, characterised by a variable surface configuration that depends on the fabrics used and the degree of brightness. Two variants of the system were presented, in two different settings: Paradise Plaza and Paseo Ponti.

The structural system was based on a repeatable 30×30 foot square module whose raised section arises from the intersection of two equal circumferences. This solution allowed the creation of a tubular reticular structure, made of steel profiles, to which taut fabric could be secured to provide shade. The entire structure is suspended by means of steel supports at its two ends, and thus does not draw attention away from the shop windows.

The design is based on the hyper architecture theory, which is all about fluidity and dynamism: a modifiable web that provides a basis for the development of the architecture.

The use of textile skin is the element that distinguishes the Paradise Plaza shading system from the Paseo Ponti one. In Paradise Plaza, the textile skin completely surrounds the structural skeleton along the East-West axis. The fabric is white and perforated, thus allowing light and air to penetrate, and possibly even the branches of the trees that are envisaged for the square. The openings, with their fluid geometries, give the shading element a distinctive pattern, and also create a play of light and shade on the surface of the square.

On Paseo Ponti, along the North-South axis, the textile shading system instead consists of triangular shapes secured to a metal structure which unfolds like a long ribbon, wrapping itself around the entire suspended structure, but leaving gaps to let the light in. At night, the fabric creates an unusual play of reflections with the artificial lights envisaged along the mall (fig. 2-3).

More recent experiments have seen the installation of permanent shading systems in newly constructed contemporary spaces, with shading emerging as an integral part of the process of planning urban spaces or, as in the case of this year’s Venice Architecture Biennale, as a form of art installation.

The first category includes the shading systems installed, also as urban design elements, in Lisbon’s relatively recently constructed Parque das Nações area, specifically in the space opposite the Oceanarium (fig. 4).

Here, a series of yellow/orange coloured “textile trees”, with square bases set on white pillars, open upwards like inside-out umbrellas, affording patrons and tourists protection from the baking sun that beats down on the large square. The intrados of these “textile trees” is illuminated by upward facing lights positioned at the top of the shaft. The path defined by the trees is punctuated with rest areas furnished with colourful striped concrete seats in yellow/blue and white/blue, set opposite each other, as in a perfect urban living room.

The Danish hall at this year’s Venice Architecture Biennale marks the collaboration between the international design studios BIG, Praksis Arckitecter, CITA and Vandkunsten, which are responsible for the four selected projects installed inside and outside the hall. Each project addresses a specific topic relevant to future development and innovation, including construction, identity, mobility and new tools. The imposing installation by CITA (Center for Information Technology and Architecture, the research centre of the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts in Copenhagen) at the entrance to the hall illustrates the potential for the development of new, digital interdisciplinary design and construction methods.

The installation’s organic form envelops part of the neoclassical Danish pavilion, located in the gardens. Made up of custom-made fabrics reinforced with fiberglass bars, the system is an elaborate tent-like structure, whose translucent fabric and fiberglass rods bend, as a result of tension and compression loading, to embrace the central corridor of the hall and the various parts of its portico. Although this parasite installation is dependent on the hall, it is nevertheless possible to envisage its application in other settings, where it might be given permanent foundations, or become part of an integrated façade system. The fact that each textile panel contributing to the organic form is unique can be taken as an allusion to the freedom offered by computational modelling — the input variables can be moved according to the given context, allowing the generation of infinite iterations. The name of the project, Isotropia, is a reference to the balance between the structure, the material and the site conditions. Isotropia was created using a new software tool, K2 engineering, which makes it possible to design, forecast, analyse and refine the performance of materials, reducing the inefficiencies encountered when using traditional construction methods. Traditional tools involve labour-intensive manual prototyping and iterative structural calculation, with analysis deferred to the final stages. Instead, by using modelling systems from the outset, it is possible to integrate structural and material analysis into the initial design process, thereby opening the way for architecture in which material behaviours are understood, and this understanding is actively applied (B. Wells, Arcspace, 2018).

Digital technologies have rapidly and radically altered our ability to conceptualise, design and manufacture materials and forms, and they therefore offer many possibilities for material and architectural innovation. But this process also demands a fluidity that is difficult to marry with the rigid structures of this field, and its tendency to assign new tools to specific actors and specific work phases. What will happen when digital tools challenge the players in the construction industry, encroaching on their territory, and when the various design and construction stages start to merge and become less well defined? What new innovation opportunities will emerge once architectural thinking enters into symbiosis with computational modelling and material manufacturing?